There’s something magical about building your first radio receiver. You connect a few components, attach an antenna, and suddenly you’re pulling voices and music out of thin air. The 4-transistor pocket radio is one of the best beginner projects for understanding how radios actually work.

This circuit is a classic superheterodyne AM receiver that uses just four transistors to capture broadcast radio signals. It’s simple enough to build in an afternoon but sophisticated enough to teach you real radio engineering principles. Let me walk you through how this circuit works and how you can build one yourself.

What Makes This a Superheterodyne Receiver?

Before diving into the circuit details, you need to understand the superheterodyne principle. It’s the architecture used in almost every radio receiver made since the 1930s, from pocket radios to modern smartphones.

The basic idea is this: instead of trying to amplify and detect the radio signal at its original frequency (which could be anywhere from 530 kHz to 1600 kHz for AM broadcast), we convert all incoming signals to a fixed intermediate frequency (IF). In this circuit, the IF is typically 455 kHz or 465 kHz.

Why bother with this conversion? Because it’s much easier to build a high-gain, selective amplifier at one fixed frequency than to build one that works well across the entire broadcast band. The superheterodyne approach gives you better sensitivity and selectivity.

Circuit Architecture Overview

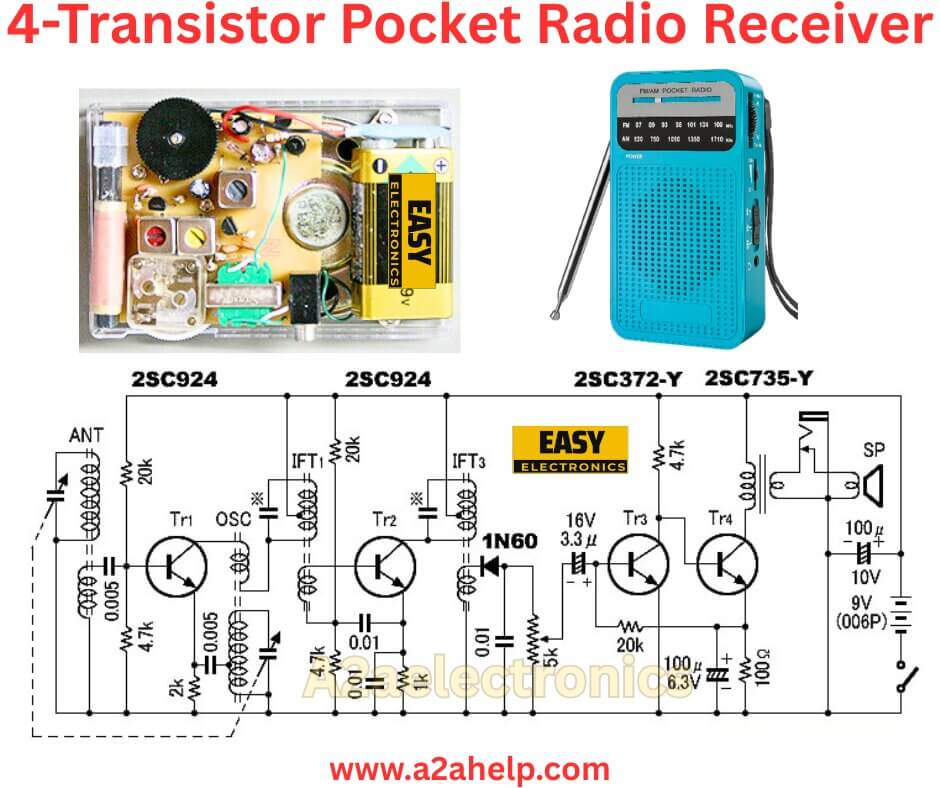

Looking at the schematic, this radio breaks down into four main sections, each handled by one transistor:

- RF Amplifier and Mixer (first 2SC924)

- Local Oscillator (second 2SC924)

- IF Amplifier (2SC372-Y)

- Audio Amplifier/Detector (2SC735-Y)

The signal flows from left to right: antenna to RF stage, through mixing, IF amplification, detection, and finally to the speaker.

The Front End: RF Amplifier and Mixer

The first transistor (2SC924) serves double duty as both an RF amplifier and a mixer. The incoming signal from the antenna passes through a tuned circuit (the ferrite rod antenna and variable capacitor) that selects which station you want to receive.

The 2SC924 is a general-purpose NPN transistor with good high-frequency performance. It amplifies the weak signal from the antenna and mixes it with the local oscillator signal. This mixing process creates two new frequencies: the sum and difference of the RF and LO frequencies. We keep the difference frequency, which is our 455 kHz IF signal.

The transformer labeled “Tr1 OSC” couples the RF stage to the next stage while also providing some selectivity. The 20k resistor and 47k resistor set the bias point for the transistor, determining its operating point and gain.

Local Oscillator Circuit

The second 2SC924 operates as a local oscillator. Its job is to generate a stable sine wave at a frequency of 455 kHz above whatever station you’re tuned to. If you’re listening to a station at 1000 kHz, the oscillator runs at 1455 kHz.

The oscillator frequency is controlled by the same variable capacitor (gang-tuned with the input circuit) and another coil in the “Tr1 OSC” transformer. This ganged tuning is crucial because it keeps the oscillator tracking exactly 455 kHz above the received frequency as you turn the tuning dial.

The oscillator uses positive feedback through the transformer to sustain oscillation. The 2k resistor in the emitter provides stabilization, while the 47k resistor sets the collector bias. The small capacitors around the oscillator circuit help determine the oscillation frequency and filter out unwanted harmonics.

IF Amplifier Stage

After mixing, we have our signal converted to 455 kHz. The third transistor (2SC372-Y) amplifies this IF signal. The 2SC372-Y is specifically chosen for its good gain at intermediate frequencies.

The IF transformer (IFT1) between the mixer and IF amplifier provides selectivity. These IF transformers are pre-tuned to 455 kHz and contain tuned circuits that reject signals at other frequencies. This is what gives the radio its ability to separate stations.

IFT2 and IFT3 (shown in the schematic) provide additional filtering and coupling. Each IF transformer adds more gain and improves selectivity. The 1N60 germanium diode and associated components form the detector that extracts the audio signal from the IF carrier.

The 20k resistor at the collector and biasing network set the operating point of this stage for maximum gain without distortion.

Detector and Audio Output

The 1N60 germanium diode is the detector. It performs amplitude demodulation, converting the 455 kHz AM signal into audio frequencies. Germanium diodes like the 1N60 are preferred over silicon diodes for AM detection because they have a lower forward voltage drop (about 0.3V vs 0.6V), making them more sensitive to weak signals.

After detection, the audio signal is extremely weak, typically just a few millivolts. The final two transistors (2SC372-Y as Tr3 and 2SC735-Y as Tr4) form a two-stage audio amplifier.

The 2SC735-Y output transistor drives the speaker directly. Looking at the schematic, there’s an output transformer coupling the final transistor to the speaker. This transformer matches the relatively high output impedance of the transistor to the low impedance of the speaker (typically 8 ohms).

The 100µF capacitor at 6.3V in the audio stage couples the audio signal while blocking DC, and the 100µF at 10V at the output does the same for the speaker connection.

Power Supply Considerations

This radio runs on 9V, supplied by a standard 9V battery (the type marked as 006P). Battery drain is modest because the total current consumption is probably only 5-10 mA, giving you many hours of listening time from a single battery.

The 16V 3.3µF capacitor shown in the schematic is the main power supply filter. It smooths out any noise on the supply rail that might otherwise be amplified and heard as a hum in the speaker.

Component Selection and Substitutions

Transistors

The 2SC924 transistors in the RF and oscillator stages need good high-frequency performance. If you can’t find 2SC924s, you can substitute 2SC945, 2N3904, or similar general-purpose NPN transistors with transition frequencies above 100 MHz.

The 2SC372-Y for the IF stage can be replaced with 2SC945 or 2N3904. The “Y” suffix typically indicates a gain grouping or selection, but standard versions work fine.

For the output stage, the 2SC735-Y can be substituted with 2SC828, 2N3904, or similar transistors capable of delivering 20-30 mA to the output transformer.

Diode

The 1N60 germanium diode is somewhat hard to find these days. You can use 1N34A, 1N270, or even a BAT85 Schottky diode as substitutes. Avoid regular silicon diodes like 1N4148 for the detector because their higher voltage drop reduces sensitivity.

IF Transformers

The IF transformers are the trickiest parts to source. They need to be tuned to 455 kHz (or 465 kHz if you use those standards). You can salvage them from old AM radios or buy new old stock (NOS) parts from electronics surplus suppliers. Make sure all your IF transformers are tuned to the same frequency.

Variable Capacitor

The tuning capacitor needs to be a dual-gang type with both sections tracking together. Typical values are 365pF per section. These are also best salvaged from old radios or purchased as NOS parts.

Building the Radio

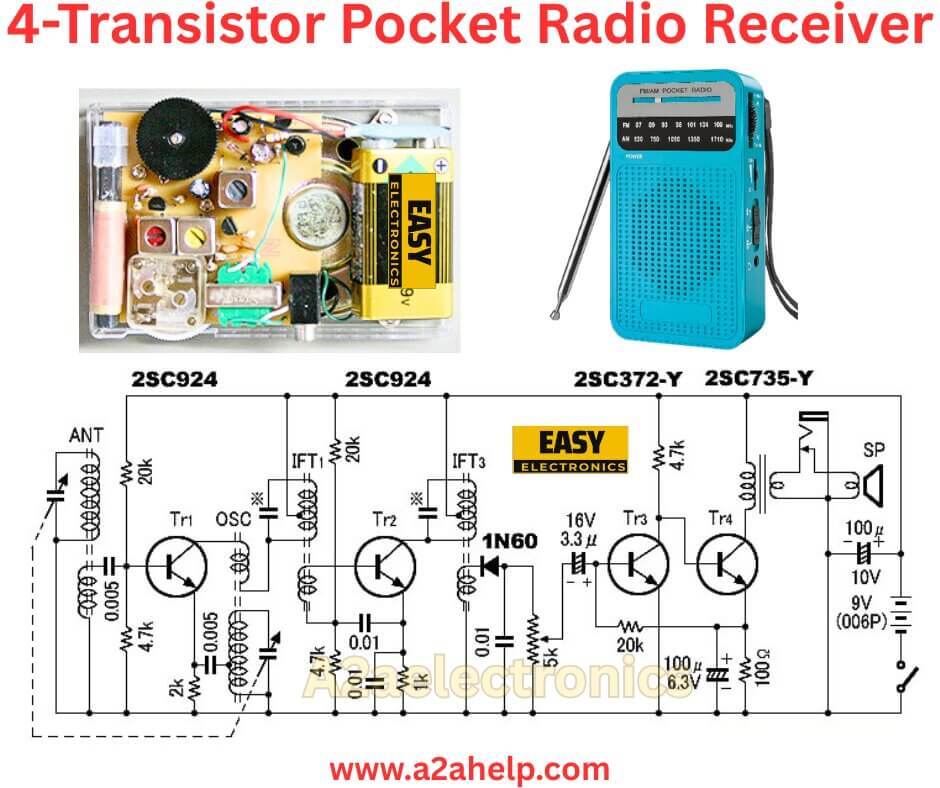

The physical construction shown in the photo uses a piece of perfboard or PCB. Point-to-point wiring works well for this circuit because frequencies are relatively low and lead lengths aren’t super critical.

Layout Considerations

Keep the RF and oscillator sections physically separate from the audio stages. This prevents feedback that could cause oscillation or instability. The ferrite rod antenna should be positioned away from the IF transformers to avoid magnetic coupling.

Ground connections matter in radio circuits. Use a proper ground bus or ground plane. Connect all ground points to this common ground, especially the negative battery terminal, emitter resistors, and bypass capacitors.

The Ferrite Rod Antenna

The antenna shown in the circuit is a ferrite rod with a coil wound around it. This is a loopstick antenna, standard in pocket radios. The ferrite concentrates the magnetic field from radio waves, making the antenna much more effective than a simple air-core coil would be.

You can buy ready-made ferrite rod antennas, or wind your own. A typical ferrite rod is 100-200mm long and 10mm in diameter. Wind about 60-80 turns of fine enameled wire (28-32 AWG) for the main antenna coil. The exact number of turns works with your variable capacitor to cover the AM broadcast band.

Alignment and Tuning

Once built, the radio needs alignment. This is the process of adjusting the IF transformers and oscillator coil for best performance.

You’ll need a signal generator and ideally a frequency counter or another working radio for reference. Set the generator to 455 kHz (or your IF frequency) and inject it at the base of the first IF amplifier. Adjust the IF transformer cores for maximum output at the speaker while monitoring with an oscilloscope or just by ear.

Next, tune the oscillator. Set your signal generator to a known frequency in the broadcast band (like 1000 kHz). Adjust the oscillator coil slug until you receive the signal when the tuning dial is set to 1000 kHz. Check at both ends of the band (550 kHz and 1600 kHz) and make small adjustments to get tracking across the full band.

Expected Performance

Don’t expect this simple radio to rival a modern digital receiver, but you should be able to pick up strong local AM stations clearly. Sensitivity depends heavily on your location, antenna orientation, and the quality of your IF transformers.

In a city with nearby AM broadcast stations, you might receive 5-10 stations with good audio quality. The selectivity won’t be great, so closely spaced stations (within 20-30 kHz) will interfere with each other.

Audio quality is typical of small AM radios: limited frequency response, some background noise, but perfectly adequate for voice broadcasts and most music. The small speaker and simple audio amplifier limit fidelity, but that’s part of the vintage radio charm.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

No reception at all: Check the battery voltage first. Verify that the oscillator is running by bringing another AM radio close to your project. You should hear a squeal or whistle from the other radio as you tune your project’s dial. If the oscillator isn’t running, check the oscillator coil connections and transistor bias.

Weak reception: Poor IF transformer alignment is usually the culprit. Carefully adjust each IF transformer core for maximum signal. Make sure the antenna coil is properly connected and the ferrite rod is in good condition.

Distorted audio: Check the bias on the audio amplifier transistors. Too much current causes distortion, while too little reduces volume. Verify all electrolytic capacitor polarities.

Squealing or oscillation: This indicates unwanted feedback between stages. Improve grounding, check component placement, and add small bypass capacitors (0.01µF) from supply rails to ground near each transistor.

Can’t tune across the full band: Oscillator tracking is off. Adjust the oscillator coil and possibly trim the oscillator section of the variable capacitor.

Learning from This Project

Building this radio teaches you several important concepts:

Superheterodyne architecture: This design principle dominates radio engineering and appears in WiFi, cellular, GPS, and broadcast receivers.

Oscillators and mixing: Understanding how frequencies mix and create sum and difference products is fundamental to RF engineering.

Impedance matching: The transformers throughout the circuit match impedances between stages for maximum power transfer.

Tuned circuits and selectivity: The interaction between inductors and capacitors to select specific frequencies is essential knowledge.

Modernizing the Design

While this 4-transistor design is educational, you could improve it with modern components. Replace the discrete IF transformers with a ceramic filter for better selectivity and stability. Use a CD2003 or similar AM radio IC for the IF and audio stages, reducing component count.

You could also add automatic gain control (AGC) to prevent overload from strong stations, or build a proper tone control circuit for the audio output.

Final Thoughts

This 4-transistor pocket radio is a window into radio engineering fundamentals. It’s simple enough to understand completely but sophisticated enough to actually work well. The fact that you can build a functioning radio receiver with four transistors, some coils, capacitors, and resistors is pretty remarkable.

Yes, you can buy an AM radio for a few dollars, but you won’t learn anything doing that. Building one yourself gives you insights into how wireless communication actually works. Plus, there’s real satisfaction in listening to a radio station on a receiver you built with your own hands.

Whether you’re a student learning electronics, a hobbyist interested in vintage radios, or someone who just enjoys understanding how things work, this project delivers. The skills you develop here translate directly to more complex RF projects like FM receivers, transmitters, or even software-defined radio.