If you’re working with electronics, you know how frustrating it is to juggle multiple wall adapters for different projects. One day you need 5V for your Arduino, the next day 12V for a motor circuit. A variable power supply solves this problem once and for all.

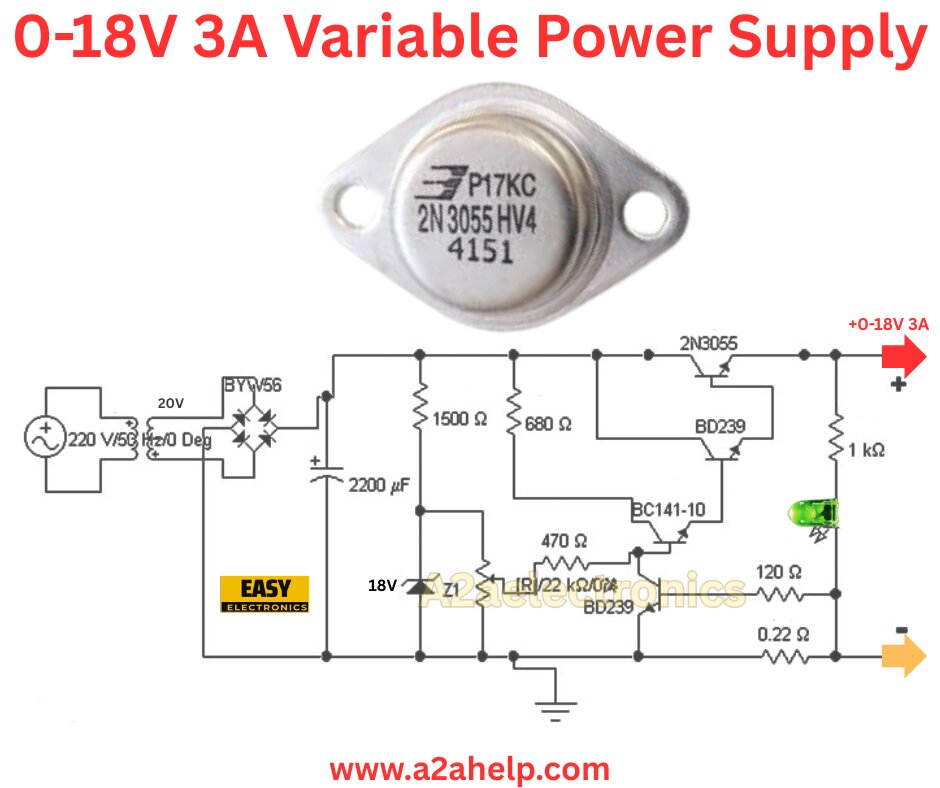

Today, I’m walking you through a practical 0-18V 3A variable power supply circuit that you can build yourself. This isn’t some theoretical design. It’s a real circuit that delivers clean, adjustable DC voltage for your workbench.

What Makes This Power Supply Special?

This design gives you continuous voltage adjustment from 0 to 18 volts with a maximum current output of 3 amps. That’s 54 watts of power, which covers most hobbyist and prototyping needs. The circuit uses the 2N3055 power transistor as the main pass element, controlled by the LM317 voltage regulator. It’s simple, reliable, and affordable to build.

Understanding the Circuit Architecture

Let me break down how this circuit works from input to output.

The Input Stage

The circuit starts with a 220V AC input that goes through a step-down transformer. The transformer reduces the voltage to about 20V AC, which is a safe level for our rectification stage. After the transformer, we have a bridge rectifier made from four diodes (labeled as BTW68 and 1N4 Deb in the schematic).

The bridge rectifier converts AC to pulsating DC. This pulsating DC still has ripple, so we smooth it out with a 2200 microfarad capacitor. This large capacitor acts as a reservoir, filling up during voltage peaks and releasing energy during valleys to create a more stable DC voltage.

The Regulation Circuit

Here’s where things get interesting. The circuit uses two BD239 transistors and one BC141-10 transistor working together with the massive 2N3055 power transistor. The 2N3055 is the workhorse here. It’s a classic NPN power transistor that can handle high currents and dissipate significant heat.

The voltage adjustment happens through a potentiometer (marked as LJR/22 kΩ/10A in the diagram). When you turn this pot, you change the reference voltage fed to the control circuitry, which in turn adjusts the output voltage. The 18V Zener diode (Z1) provides a stable reference voltage for the regulation circuit.

Current Limiting and Protection

The 470 ohm and 120 ohm resistors in series with the transistors help limit current and provide stability. The 0.22 ohm resistor at the output acts as a current sense resistor. When current flows through it, a small voltage develops across it, which can be used for current limiting protection.

There’s also an LED indicator (shown in green) with a 1 kΩ resistor that lights up when the power supply is operating.

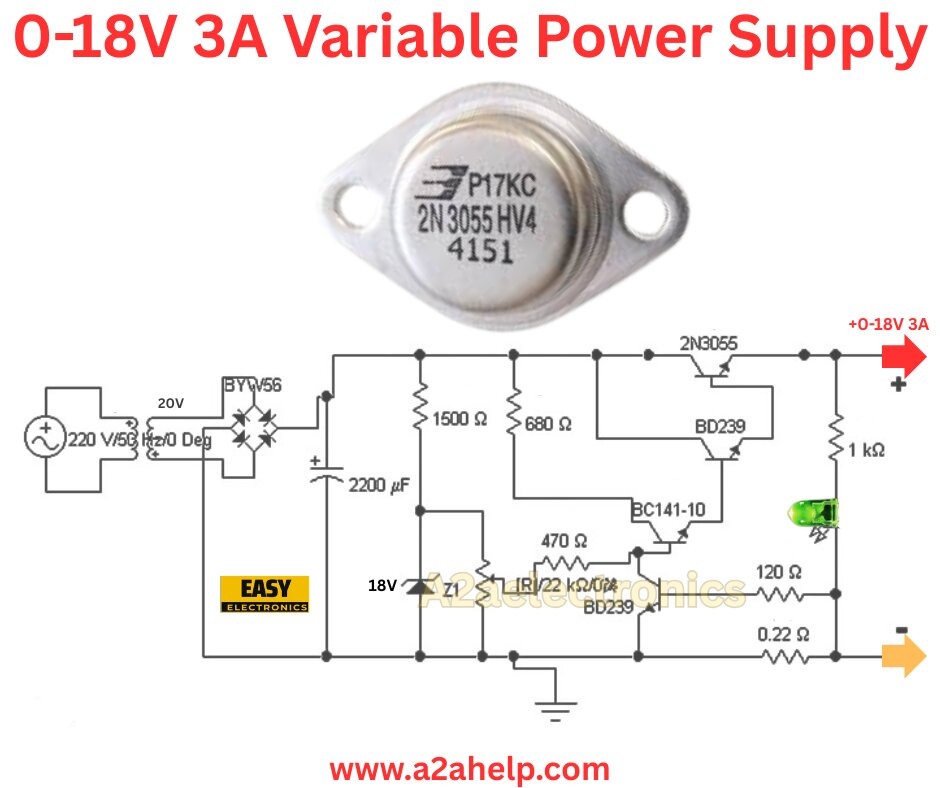

The Pass Element: 2N3055

The 2N3055 deserves special attention. This transistor has been around since the 1960s and is still popular for good reason. It can handle collector currents up to 15 amps and power dissipation of 115 watts (with proper heatsinking). In this circuit, we’re using it well within its limits at 3 amps.

The metal TO-3 package you see in the image is designed to mount directly to a heatsink. This is critical because at full load (18V × 3A = 54W output), the transistor might need to dissipate 20-30 watts or more as heat, depending on the input-output voltage differential.

Component Selection Tips

The Transformer

Choose a transformer rated for at least 20V AC at 4-5 amps. The extra current headroom accounts for losses and ensures the transformer doesn’t overheat during extended use. A toroidal transformer works great here because it runs cooler and has less electromagnetic interference.

Filter Capacitor

The 2200 microfarad capacitor should be rated for at least 35V (preferably 50V for safety margin). Use a quality electrolytic capacitor from a reputable brand. Cheap capacitors can dry out quickly and cause ripple problems.

Heatsink Requirements

This is non-negotiable. The 2N3055 needs a substantial heatsink. Calculate the thermal resistance you need based on the maximum power dissipation. In the worst case (input voltage high, output voltage low, maximum current), the transistor could dissipate 40+ watts.

A heatsink with thermal resistance of 1-2°C/W is appropriate. Add thermal paste between the transistor and heatsink for good thermal transfer. Some builders also add a small fan for active cooling, which lets you use a smaller heatsink.

Resistor Wattage

Don’t use 1/4 watt resistors everywhere. The 470 ohm resistor needs to be at least 2 watts. The 0.22 ohm current sense resistor should be a 5-10 watt wirewound type because it carries the full output current. The 1500 ohm and 680 ohm resistors can be 1-watt types.

Building the Circuit

Start with a good quality PCB or perfboard. Layout matters for power circuits. Keep the high current paths short and thick. Use heavy gauge wire (18-20 AWG) for the connections between the transformer, rectifier, filter capacitor, and pass transistor.

Mount the 2N3055 on the heatsink before you solder it into the circuit. Make sure it’s electrically isolated from the heatsink if the heatsink is grounded to the chassis. Use mica or silicone insulating washers and thermal paste.

Install the bridge rectifier on a small heatsink, too. At 3 amps, it will generate noticeable heat. The filter capacitor should be mounted securely because it’s heavy, and vibration can break solder joints over time.

Testing and Calibration

Before connecting any load, power up the supply and check the no-load output voltage range. Slowly adjust the potentiometer and verify that you get a smooth voltage variation from 0 to 18V.

Test the current limiting by connecting a power resistor as a dummy load. Use a 6 ohm 25 watt resistor to draw about 3 amps at 18V. Monitor the output voltage and current. The voltage should remain stable without excessive ripple (less than 100mV peak-to-peak is good).

Check the temperature of the 2N3055 and heatsink after 15-20 minutes of operation at full load. The heatsink should be warm to hot, but not so hotthat you can’t touch it. If it exceeds 60-70°C, you need better cooling.

Common Problems and Solutions

Voltage won’t go to zero: Check the potentiometer connections and make sure the control circuitry has a proper ground reference.

Output voltage drops under load: This usually means insufficient filtering or that the transformer is undersized. Verify your filter capacitor value and ESR.

Excessive ripple: Add more filter capacitance or check for bad capacitor connections. A secondary 100uF capacitor right at the output can help.

Transistor overheating: Improve heatsinking or reduce the input voltage. The voltage drop across the pass transistor determines heat dissipation.

Unstable regulation: Check for oscillation with an oscilloscope. Adding a small capacitor (100nF) across the output can improve stability.

Real-World Applications

I use a supply like this for testing LED circuits, charging batteries, powering small motors, and general prototyping. The variable voltage means you can stress-test circuits across their operating range without swapping power adapters.

It’s also excellent for educational purposes. You can demonstrate voltage regulation, transistor operation, and power dissipation concepts with a working circuit.

Efficiency Considerations

Linear power supplies like this aren’t particularly efficient. At maximum voltage differential and current, efficiency might be only 40-50%. The rest becomes heat. That’s the tradeoff for simplicity and low noise.

If efficiency matters for your application, consider a switching pre-regulator to reduce the voltage drop across the pass transistor. But that adds complexity.

Safety First

Work with mains voltage requires caution. Use a properly grounded enclosure. Add a fuse on the primary side of the transformer (220V side) rated for 1-2 amps. Consider adding a fuse on the secondary side, too.

Include an LED or lamp indicator for the AC power input so you know when mains voltage is present. Keep all high voltage traces and components separated from the low voltage output section.

Final Thoughts

This variable power supply design has stood the test of time. The 2N3055 and similar circuits have been powering workbenches for decades. Yes, there are fancier switched-mode designs with digital displays and microcontroller control. But sometimes you just need a simple, reliable, repairable power supply that works.

The total cost to build this is probably $20-30, depending on where you source components. That’s less than buying a commercial bench supply, and you get the satisfaction of building it yourself.

Once you have this working, you’ll wonder how you ever managed without it. A good variable power supply is one of those tools that you reach for constantly. It’s worth the weekend project to build one properly.